ANZAC Dawn Service 2019 speech: Pink Telegrams

Pink telegrams

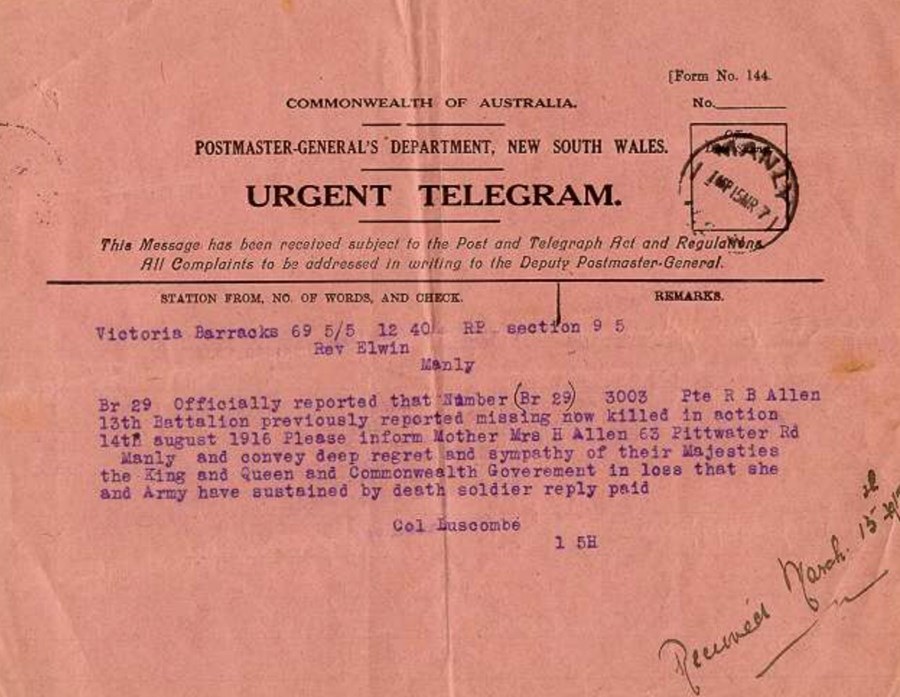

The telegrams that delivered bad news were pink.

Today pink is not a colour of loss.

Not a colour of sadness.

Or fear. Or terror. Or finality.

But during the Great War, the telegrams which broke the worst news were typed on pink paper.

The colour became a silent warning of the anguish that was about about to be unleashed. A knock, a door opened and the pink could be seen before a word was said.

Sometimes it was a junior postal clerk, a child by today’s measure, who may very well have known, may very well have looked up to, the person whose grim story was written on pink.

Often the telegram was delivered first to a local clergyman, who would make his way to the home of the family to deliver the news.

The pink telegram took three possible paths: missing, injured, deceased.

If a telegram said that your son was missing, you could dismiss it as inaccurate, uncertain, surely to be proven wrong. You could lace the brief words with a frail hope.

If a telegram said that your husband was injured, the fear and dreading would grip you with a coursing malignancy. The breath stolen from your lungs as you comprehended the uncertainty of your future. From wife to carer; the convalescence; the shrivelled income; the invalidity. Yet he was still alive.

If the telegram extinguished all hope, the finality ripped through families like a tornado in a corn field. Mothers fell to their knees, wives crumpled on their beds, fathers turned and walked silently away.

The human story and the grave reality of the Great War was written in a few words on over two hundred thousand pink telegrams: 60,000 men and women killed, 156,000 men and women wounded or taken prisoner.

With the succinctness of the era, these telegrams outlined the facts and if the news was the worst, they provided brief sympathies from the government and from the King and Queen.

A handful of words on a piece of pink paper, a cover note to a tragedy playing out in hundreds of communities and thousands of homes across our fledgling nation.

Yet the telegrams told very little of the story that would unfold. They told nothing of the horrors on the Western Front and gave no insight into the carnage wrought at home. They captured a moment in time, but stole the potential from a generation: the marriages left severed; the children unborn, the careers unfulfilled, the homes never built, the Christmases uncelebrated, the paths not trodden.

A century ago, in 1919, the pink telegrams began to fade, as our diggers came home.

Their return was slow, stuttering, uncertain. Many feared that it would never happen and for some it didn’t as the final few pink telegrams stole hope as illness and disease unfolded thousands of miles away and claimed the war’s final victims.

And so we gather to remember,

Not glorify.

To bow our heads,

Not wave flags.

To honour,

Not celebrate.

And we think of the people whose names were written on those pink telegrams - and the people who loved those people, and the people who didn’t get a chance to love those people.

And we give thanks for their sacrifice.